Part 1 of 3

by BK Munn

Part 1 of 3

by BK Munn

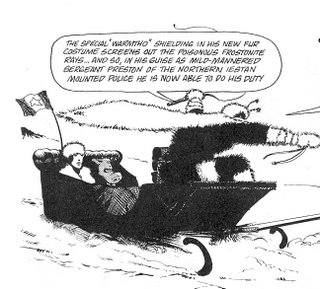

It's snowing again this morning, putting me in mind of snow in the comics. Trying to remember my experience of snow in the comics, the first thing that comes to mind is Peanuts which always was very seasonal in its rhythms. Although other daily strip cartoonists did winter-themed gags and even created snowy adventure storylines (I think the final episode of Caniff's Terry and the Pirates took place on a snow-filled runway), Peanuts is really the winter strip par excellence, a position that was ratified with the animated Christmas special back in the 1960s. Outside of the strips, U.S. kids comics creators like

John Stanley,

Carl Barks, and the

Archie gang always published season-specific issues. As well, I'm sure I read the occasional superhero comic as a kid featuring a chilly, John Romita Spider-Man brawling over snowy New York City rooftops. But the first time I think I really noticed snow as an actual presence and plot device in a graphic novel context was Cerebus.

At some point in the early 1980s,

Dave Sim seemed to decide to make snow

a major character in his High Society graphic novel. I'm sure there was snow in earlier issues since much of the series was a parody of the Barry Windsor-Smith Conan comics and I'm pretty sure there was at least one issue of Conan that featured barbarians fighting frost giants in the wilds of Hyperboria, or wherever it was that Conan was from, but Sim's use of snow in these later Cerebus issues really struck a chord with my 13-year-old self.

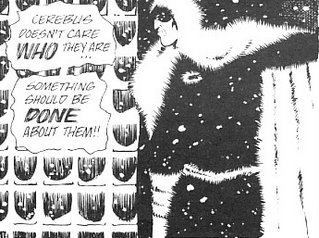

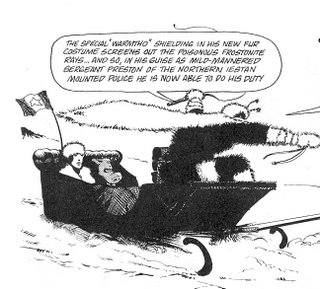

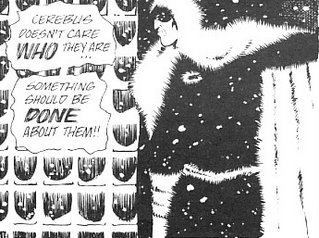

The first snow-themed issue I remember is Cerebus #44, "The Deciding Vote". Fans (or maybe just Sim) later called this the "wuffa-wuffa" issue, after the sound the lead character made when walking with snowshoes. The plot of the issue, Cerebus following an old farmer around in order to solicit the geezer's vote for Prime Minister, took a backseat to the slapstick images of Cerebus trying to navigate his way through snowdrifts and the drunken antics of Sim's superhero parody character The Roach. Y'see, Sim the artist was telling us, Cerebus's attempt to transform himself from barabarian to politician is an uphill battle and even the elements are against him.

Things only got worse for the character as the book progressed: Cerebus' time in office seemed to take place over the course of one long winter, which meant that the snow hung around. Sim seemed to take great delight in drawing the characters in the midst of blizzards or contrasting the heated conversations of his characters with the serenity and quiet of the outdoors. The story, and Cerebus' political career, culminated with an invasion of the city by barbarians. Sim told the story in a series of long panels, ending with his now-isolated character walking off into the distance into a sea of white.

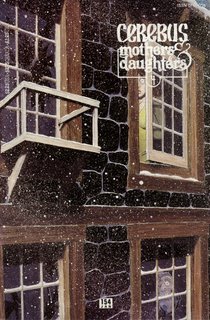

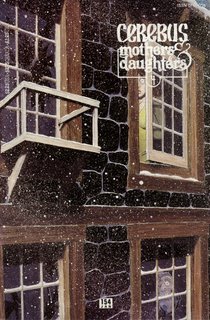

Snow popped up in the next few graphic novels as well. In Church and State, Cerebus becomes Pope, gets thrown off the side of a snow-covered mountain, and has to spend many pages climbing back up. Meanwhile, other characters stand around in the snow, looking pensive and plotting schemes of vast socio-political importance. During this time, Sim's assistant Gerhard really started to make his presence felt in the series, drawing highly-detailed walls, cityscapes, gargoyles, etc, all blanketed in layers of snow.

I think that, in part, Sim was initially sort of stuck with the northern fantasy world he had inherited from his pastiche of the world of Robert E. Howard. However, he eventually realized that he could incorporate aspects of this universe into the tale to his advantage, using the weather as a major storytelling tool (and in a black-and-white book, snow makes a nice contrast). As well, the world he was creating was starting to take on more aspects of the real world that he was interested in. I used to imagine that his fictional city state of Iest was a brilliant amalgamation of Kitchener, Ottawa, 1917 St. Petersburg, medieval Europe, Carl Bark's Duckburg, and Conan's D&D fantasyland. At the same time, I sometimes resented the enormous use of white space in Cerebus, an indication I thought of a certain amount of cartoonist laziness. And after awhile, the device takes on a strained air (not unlike the device of using a cartoon aardvark barbarian as the lead character in a 3000 page graphic novel about religion, politics, and gender relations). The depictions of falling snow still are very affecting, as long as one of Sim's gross caricatures is not in the panel, maybe because falling snow is still evocative of a certain sense of nostalgia (childhood, holidays, etc). Overall, and despite the general failings of Sim's project as a whole, I can still appreciate these early Cerebus stories for their modest attempts at depicting the Canadian landscape in graphic novel form. Really, a very sophisticated and sustained, at times subtle use of nature for such a

young artform.

Next time: the forecast calls for more snow

Part 2

Part 3