The Animated Corpse of the Working Class

by BK Munn

We

search in vain for examples of the working class superhero. With few exceptions, he is nowhere to be found. In his place, everywhere we find the figure of the superhero working on the side of the bosses, whether as an ideological footsoldier in the armies of the mass media (the Daily Planets and Bugles, WHIZ's and WXYZ's), as a representative of the Repressive State Apparatus (the

police and

armed forces), or even as the boss himself: we need not enumerate how many capitalists seem to moonlight as masked vigilantes, erstwhile Robin Hoods reduced to acting as night watchmen over the money bins of their fellow billionaires.

Ah, but who do they guard against? Who appears to play the role of

Beagle Boy opposite the concerted efforts of these super-powered

Scrooge McDucks? The superhero's triumphalist rhetoric of truth, justice, and the American Way must not remain unchallenged --nor can the use of force continue to be monopolized by a single comic book class. At last, a dim figure steps forward to take up its historic role of class antagonism.

Enter the supervillain, shambling leftward onto the world-historic stage. As an expression of class anxiety, he is unparalleled in art. From his secret origins as the stepchild of the mustache-twirling Oil Can Harry of melodrama and the grand-guignol grotesques of Dick Tracy, the comic book villain embodies all of the perceived threats to the capitalist utopias envisioned by the comic book creator, a world of shiny metropolises, lorded over by masonic fraternities of top-hatted magicians, fetishistic playboys, and patriarchal circus strongmen.

The supervillain disturbs this child-like Eden by introducing a note of the

abject to the proceedings. The supervillain, representing the poor and working class multitude, is

our window into the world of the superhero. Whether mad-scientist, gun-toting mobster, or costumed gadgeteer, the comic book villain represents "the return of the repressed" in the dream world of adolescent power fantasies. No matter how often or how ingeniously the superhero puts him down, the villainous representative of the working class schemes his way out of his prison and into a new museum heist, nuclear extortion, or revenge plot. The chief lesson of the superhero narrative is that no plot device or deus ex machina can ultimately contain the immense power of the working class, especially when organized or constituted as a corporate mass entity.

The appeal of their forceful presence is almost magnetic. What youthful reader has not experienced a comradely thrill when encountering for the first time such deliciously named amalgamations as The Monster Society of Evil, The Legion of Doom, or The Secret Society of Supervillains? These unions and guilds of the downtrodden lumpen proletariat of the comics form an essential counterpoint to the legalistic Chamber of Commerce-like aura that adheres to the clubby superhero organizations (The Justice League of America, The Avengers, et al).

Nowhere is this more evident than in this charming little epic from 1947's All-Star Comics #33. The two post-War years of 1946 and 1947 were

memorable as a time of intense class conflict, as the wartime economic boom combined with an increasingly militant U.S. working class made up of returning soldiers and a Depression-hardened nation. Some of these issues are bound to find their way into the prole art form of comics.

"The Revenge of Solomon Grundy" features the return of the

nursery-rhyme-inspired supervillain

Solomon Grundy, after a long absence. Last seen imprisoned by Green Lantern in a magical green ball, Grundy personifies the bottled-up desire of working class ambition, on hold during the "no-strike" years of World War II and still frustrated by the years of the Great Depression of the 1930s. At the same time, he represents the refusal of the disciplinary regime of the social factory system --a sort of unliving mass strike.

Grundy's attributes are those of the dreaded poor or proletariat unleashed. From his humble origins as a small-time criminal who meets his ignoble end drowned in a swamp, to his reincarnation as a monstrous, barely articulate agent of vengeance, Grundy is a proto-Hulk, equal parts lovable hillbilly and

Luddite loom-smasher. Clad in tattered working-man's clothes, including giant hobnail-style brown boots, the zombie-like Grundy stands in stark sartorial contrast to the dandified glamour of the superheroes, with their capes, primary colours, and bold trademarked insignia. He is the Other to the rich and powerful superhero, a dialectic whose hallmark is violence and confrontation.

The plot of the story is delightfully simple. Freed from his magical prison by a stray bolt of lightning, Solomon Grundy rampages through the countryside and a series of small towns in search of his arch-enemy, the superhero Green Lantern. Alerted by a radio report, the members of the Justice Society disrupt their monthly meeting and split up to search for the so-called "inhuman menace to mankind." Encountering Grundy separately, the members of the Society suffer defeat after defeat, but manage to each solve a number of local dilemmas brought to light by the appearance of the ghostly apparition of Grundy. Thus, the sound thrashing administered to The Flash is the occasion for a local police chief to redeem himself. Likewise, Dr. Midnight's narrow escape from death at the hands of Grundy results in his foiling a pair of safe-crackers.

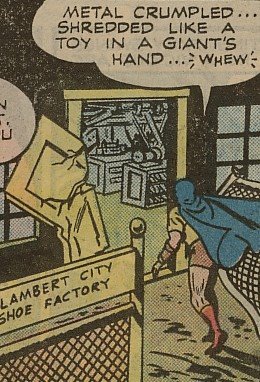

The locus of the action is largely industrial, with all of the settings having heavy ideological overtones. For instance, the heroes battle Grundy in two factories: Diminutive college student-turned costumed pugilist

The Atom engages his opposite inside a

shoe factory, where versions of Grundy's giant boots are arranged in rows and the giant seizes the means of production, as it were, to deliver a major beating. In a similar manner,

Johnny Thunder encounters a copy-cat version of Grundy at a cereal factory. The other heroes attempt to prevent Grundy's riotous war on private property in the form of a town square, a rich family's mansion, and a newspaper office, with mixed results.

The solution is total banishment: the lesson of the comics is that Grundy, aka the working class, cannot be stopped by bullets or brawn. It remains for Green Lantern to encase him in another bubble and transport him to the moon, in something of an anti-climax.

It is easy, given stories like this, to imagine Solomon Grundy as a mass or corporate figure, his part-human, part-swamp composition a dual metaphor for both the imagined threat posed by an aroused working class --a working class that can only be constrained by a concerted effort on the part of capital, utilizing all of capital's weapons-- and a repressed proletarian subjectivity, reveling in freedom and destruction. In this respect, even the efforts of a penny-a-word pulp writer like Gardner Fox and a team of teenage artists employed in sweatshop-style production, labouring over adventure stories for children, have a part to play in the ideology and iconography of class struggle.