The Guides, the Wardens of our faculties,

And Stewards of our labour, watchful men

And skilful in the usury of time,

Sages, who in their prescience would controul

All accidents and to the very road

Which they have fashion'd would confine us down

Like engines...

(Wordsworth, The Prelude)

by BK Munn

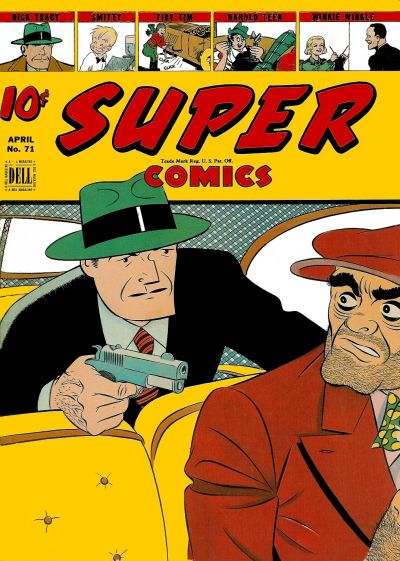

The origin of Ed Peale, alias The Gong. He’s shaped like a bell! Comic book supervillains were originally working class rebels, of course. Let's see how millionaire Bruce Wayne teams up with the cops to discipline The Gong’s revolt in ‘The Bandit of the Bells!’ (Batman #55, reprinted in Batman #198) –art by Charles Paris, 1949.

I've written before about how the villains are the only truly revolutionary --or even proletarian-- figures in superhero comic books, and here is another great example.

Here we have a supervillain after my own heart, a rebel against the false industrial time-disciplines of the school and factory punch-clock; an autodidact scholar and historian who schemes to befuddle millionaire do-gooders, banks, and the forces of order. And here we see the delicious class conflict at work within the industrial structure of DC comic book sweatshop production as well. The uncredited writer (probably the great Bill Finger) and artist Charles Paris --both working as "ghosts" for Batman creator Bob Kane, who's signature is on the title page of the story but who had nothing to do with the day-to-day creation of the comics by his "studio"-- are clearly engaging in a bit of fun with their own deadline-controlled world. The ticking clock and figurative bells of all sorts make great villains and what young reader hasn't chafed against their restrictions as against Dickens' Gradgrind?

But the battle between student/worker goes beyond the schoolyard. The Marxist historian E.P. Thompson wrote eloquently on this conflict, in an essay called "Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capital":

"In all these ways - by the division of labour; the supervision of labour; fines; bells and clocks; money incentives; preachings and schoolings; the suppression of fairs and sports —.new labour habits were formed, and a new time-discipline was imposed.) It sometimes took several generations (as in the Potteries), and we may doubt how far it was ever fully accomplished: irregular labour rhythms were perpetuated (and even institutionalized) into the present century, notably in London and in the great ports.

Throughout the nineteenth century the propaganda of time-thrift continued to be directed at the working people, the rhetoric becoming more debased, the apostrophes to eternity becoming more shop-soiled, the homilies more mean and banal. In early Victorian tracts and reading-matter aimed at the masses one is choked by the quantity of the stuff. But eternity has become those never-ending accounts of pious death-beds (or sinners struck by lightning), while the homilies have become little Smilesian snippets about humble men who by early rising and diligence made good. The leisured classes began to discover the "problem" (about which we hear a good deal today) of the leisure of the masses. A considerable proportion of manual workers (one moralist was alarmed to discover) after concluding their work were left with

"several hours in the day to be spent nearly as they please. And in what manner ... is this precious time expended by those of no mental cultivation . . . We shall often see them just simply annihilating those portions of time. They will for an hour, or for hours together ... sit on a bench, or lie down on a bank or hillock ... yielded up to utter vacancy and torpor ... or collected in groups by the road side, in readiness to find in whatever passes there occasions for gross jocularity; practising some impertinence, or uttering some jeering scurrility, at the expense of persons going by ... "

This, clearly, was worse than Bingo: non-productivity, compounded with impertinence. In mature capitalist society all time must be consumed, marketed, put to use; it is offensive for the labour force merely to "pass the time". "

These sound like some of the same critiques levelled by Wertham against the hooky clubs of juvenile delinquents who spent time away from school reading comics books!

Thompson wraps up with a glorious, utopian vision of so-called leisure time and the revolt aginst a puritan view of time-keeping:

"And there is a sense, also, within the advanced industrial countries, in which this has ceased to be a problem placed in the past. For we are now at a point where sociologists are discuss- ing the "problem" of leisure And a part of the problem is: how did it come to be a problem ? Puritanism, in its marriage of convenience with industrial capitalism, was the agent which converted men to new valuations of time; which taught children even in their infancy to improve each shining hour; and which saturated men's minds with the equation, time is money.128. One recurrent form of revolt within Western industrial capitalism, whether bohemian or beatnik, has often taken the form of flouting the urgency of respectable time- values. And the interesting question arises: if Puritanism w a s a necessary part of the work-ethos which enabled the industrialized world to break out of the poverty-stricken economies of the past, will the Puritan valuation of time begin to decompose as the pressures of poverty relax ? Is it decomposing already ? Will men begin to lose that restless urgency, that desire to consume time purposively, which most people carry just as they carry a watch on their wrists ?

If we are to have enlarged leisure, in an automated future, the problem is not "how are men going to be able to consume all these additional time-units of leisure ?" but "what will be the capacity for experience of the men who have this undirected time to live ?" If we maintain a Puritan time-valuation, a commodity-valuation, then it is a question of how this time is put to use, or how it is exploited by the leisure industries. But if the purposive notation of time-use becomes less compulsive, then men might have to re-learn some of the arts of living lost in the industrial revolution: how to fill the interstices of their days with enriched, more leisurely, personal and social relations; how to break down once more the barriers between work and life. And hence would stem a novel dialectic in which some of the old aggressive energies and disciplines migrate to the newly- industrializing nations, while the old industrialized nations seek to rediscover modes of experience forgotten before written history begins."

Heady stuff for a children's Batman comic book, but this is the genius of The Gong!