Friday, December 26, 2008

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

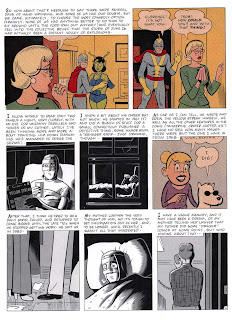

Holiday Fun: Nardwuar is a Canadian Superhero

See the Canadian punk king rock out while dressed as Marvel Comics' Canadian superhero The Guardian:

Monday, November 10, 2008

Top 5 Fictional Comic Books

I recently read with interest this examination of books that never existed outside of fiction on the Guardian Book Blog. In that discussion of Borges-style imaginary books like The Blind Assassin from the Margaret Atwood novel of the same name, a poster in the comments section mentioned several apocryphal novels glimpsed fleetingly in a sequence from Neil Gaiman's Sandman comic book. The post made me think about my favourite examples of "fictional" comic books and cartoon characters, as featured in some classic comics and graphic novels.

5. "The Comic Book Archer" (Adventure Comics 269) by Robert Bernstein and Lee Elias

In this 1960 story, superhero and Robin Hood imitator Green Arrow tries to help a young comic book artist get published in "All-Star Comics" by reproducing the feats of the cartoonist's creation, "Wizard Archer." This is a fun little gem from the Silver Age of U.S. comics that features a self-referential, behind-the-scenes peek at a DC-like comics company, in which caricatures of writer Robert Bernstein and cartoonist Lee Elias appear to explain how comic books are made ("The artists draw whatever the writers tell them to in their scripts!"). Of course, the upshot is that Green Arrow proves the archery tricks that appear in the comic can actually be accomplished in "real life" and so Wizard Archer appears in the next issue of All-Star, which finds a space on the shelves alongside Atlantis Comics, The Golden Avenger, and Western Heroes. (this story is reprinted in Showcase Green Arrow)

4. Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons (DC)

The comic-within-a-comic of this graphic novel is the famous Tales from the Black Freighter, the pirate comic and Brecht-reference that answers the question, what kind of comics would kids read in a world where superheroes are real? Text pieces in the book suggest that Tales was part of a larger pirate genre, spear-headed by EC's Piracy. The pirate story "Marooned" is used by Moore as part of the elaborate system of parallels and gothic devices that make up the bally-hooed structure of Watchmen and still reads today as an affecting piece of purple prose, regardless of the repellent stiffness of Gibbons drawings.

3. Hicksville by Dylan Horrocks (Drawn and Quarterly)

This graphic novel about an American journalist investigating the bizarre secrets of a small New Zealand town is equal parts ode to comics and metatextual exegisis of comics storytelling. It also contains more than its fair share of imaginary comics (or comics-within-comics), including Captain Tomorrow -- the creation of New Zealand ex-pat Dick Burger, an autobiographical minicomic by Burger's ex-assistant Sam Zabel, and mysterious about maps, Maori, and Captain Cook. At the heart of the book lies the mystery of the Hicksville Lighthouse, repository of all of the great comic might-have-beens, the mythical comics that the world's greatest artists and writers would have created if not constrained by commerce and the philistinism of comic book production in the 20th Century. Thus, we are treated to the exquisite idea of Harvey Kurtzman's magnum opus History of War, lying alongside lost works by Jack Kirby, Picasso, Winsor McCay, and untold hundreds of others.

2. David Boring by Daniel Clowes (Pantheon)

This graphic novel has been described by Clowes as "Fassbinder meets half-baked Nabokov on Gilligan's Island" and largely resists summarization. It deals in small part with efforts of the eponymous lead to learn more about his father, a cartoonist who worked on a superhero comic book called The Yellow Streak. The single extant issue of the comic book exists only in fragmented form, having been torn up by Boring's mother. Piecing together the few panels of the comic remaining, it appears that the Yellow Streak comic is a synthesis of Superman and Johnny Thunder, but the story is mostly unreadable, portraying a weird Freudian nightmare universe akin to the world created by Wayne Boring and other artists of the Weisinger-era Superman comics, the world of Jimmy Olsen and the Phantom Zone. Boring's efforts to make sense of these fragments, trying to find some reference to the real world history or psyche of his father form one of the major subplots of the book and relate to Clowes' recurring themes of alienation and authenticity.

1.

Wimbledon Green by Seth (D+Q)

Seth's first graphic novel, It's a Good Life If You Don't Weaken, introduced us to the fictional New Yorker cartoonist Kalo, one of the great hoaxes of modern comics. Seth wrote an introduction to Horrock's Hicksville and seems to have a soft spot for imaginary comics. Wimbledon Green is the story of an Uncle Scrooge-like comic collector who criss-crosses the country looking for the world's most rare and obscure comics, including such gems as The Green Ghost #1 (the Holy Grail of comics collectors), All Bedtime Comics and Mighty Orbit. But the cream of Wimbledon Green's collection is the classic hobo comic book, Fine and Dandy, a wonderful series that recalls 30s comic strips, Laurel and Hardy, and the work of John Stanley, a Seth touchstone and idol.

Monday, October 13, 2008

Review: Manga Serials

I missed out on responding to Tom Spurgeon's most recent "5 for Friday" questionnaire, Right to Left, or, "Name Five Manga Series You Personally Are In The Midst Of Reading, Whether Or Not The Series Is Ongoing Or Finished." Since the last time I reviewed a random manga title was awhile ago, I thought I'd respond to Spurgeon's quiz here:

The most recent translated Japanese comic I read was Seiichi Hayashi's Red Colored Elegy, a wonderfully evocative existential graphic novel about two young lovers in 1970s Japan, which the comics critic Bill Randall has suggested owes a large debt to gegika pioneer Yoshiharu Tsuge. But this is a stand-alone novel, and one of the better ones I've read this year. In terms of multi-volume stories, however, my reading has generally been limited to adolescent and melodramatic genre fare.

1. Cat-Eyed Boy and The Drifting Classroom, by Kazuo Umezu

The beautifully packaged Cat-Eyed Boy (published by VIZ) tells the story of the titular feline demon, equal parts Tintin, Sluggo, Ditko-era Peter Parker, and Klarion the Witch-Boy, an itinerant monster-fighter who enjoys living in people's attics and defending children and their families (usually against their will) from (sometimes quite disturbing) manifestations of evil. Cat-Eyed Boy is a perfect serial character (the stories originally ran in a kids magazine with a horror edge, a fact referred to in several episodes), with a built in appeal to younger readers centred on the hero's rejection by society as well as a childlike approach to plot and narrative logic, not to mention horrific, "I dare you to look"-style imagery. The stories are disgusting, scary, hilarious, and emotionally powerful. I burned through the two-volume omnibus edition of these books, and the horrific images, humour, and cartooning artistry have stayed with me. The amazing, Willy Wonka-flavoured book design is discussed by Chris Butcher here).

By contrast, I am slowly savouring Umezu's magnum opus, The Drifting Classroom, ordering two volumes at a time and waiting anxiously between installments (I've just finished volume 6). The story, about an entire school of Japanese children mysteriously transported to a post-apocalyptic future, and the resulting Lord of the Flies-style debacle that ensues, is a breakneck, fast-paced horror-thriller about loyalty, familial love, politics, savage murder, giant insect creatures, Plague, and the howling fear of imminent, inevitable dirty death. The original serial nature of the work shows in its overall frantic pace, where events tumble over each other, unchecked, with very little in the way of pacing, reflection or character development. But it is thrilling, sad, and spooky.

2. Dororo by Osamu Tezuka

I've only read the first volume of Vertical's 3-volume collection of this disturbing 1960s Tezuka classic, written in the vein of Kurosawa meets Frankenstein. The story, about a young urchin who teams up with a ronin, who is really a bizarre Pinocchio-like character whose body parts have been stolen by demons, is gross and mesmerizing, with great storytelling and Tezuka's patented cross-genre goofiness. The book design of this series, like most of Vertical's offerings, is beautiful.

3. Nana by Ai Yazawa

I first became aware of Nana, a sort of punk soap opera several levels below, continents and generations removed from Love and Rockets, by flipping through the pages of Shojo Beat magazine at the grocery store a few years ago. The most accessible, recognizingly human, and serious of the many girls' manga series on the market in North America that I've encountered, the story, about two young women trying to make it in the big city, is compelling, humourous, and sharply-drawn. Very much a melodrama, the book packaging of the first two volumes I have is reflective of the intended audience, with muted colors and thoughtful imagery.

4. One Piece by Eiichiro Oda

This serial is one of the very few boys' series I can even stand to look at in Shonen Jump magazine, thanks to the open, fluidly dynamic and cartoony style of writer-illustrator Oda. The story, about a Plastic Man-empowered wannabe boy-pirate in search of a mythical magic coin with his Jason and the Argonauts/Seven Samurai company of super-powered fighters (think Jimmy Olsen meets the plot of Fantastic Four #5, forever), is strictly pulp boilerplate and shows no sign of ending soon (there are over 50 volumes). Moronic and basically for kids, it is nevertheless one of the most coherent and appealing of the popular comedy-adventure fight comics.

5. Death Note by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata

I am "in the midst of reading" this series only in the sense that I stopped before finishing the final volume. At the time of first reading, the series just became too cyclical and frustrating, after a pivotal set-back/do-over half-way through where a major protagonist was replaced by a younger variation of himself. The series, about a highschool student who is granted the demonic power to kill people at a distance by writing their name in a notebook, is a tense, page-turner of a gothic thriller, relentless in its pacing, and full of agonizing reversals, hairbreadth escapes, gasp-inducing shocks, moral quandaries, and crazy-explosive Hollywood set-pieces. The Byzantine story and plot mechanics are very nicely complimented by the laser-sharp daring of Obata, a virtuoso cinematographer to writer Ohba's Hitchcock-ian plodding.

Wednesday, October 01, 2008

Review: How Sluggo Survives

How Sluggo Survives

Ernie Bushmiller, edited by James Kitchen

Kitchen Sink Press

1989

ISBN 0-87816-067-1

out-of-print, price my vary

I found this book as part of a Mystery Hoard that included, in total, 3 issues of Wizard Magazine and a giveaway Spider-Man comic.

How Sluggo Survives is a collection of Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy comic strips that focuses on Nancy' co-star and sometime boyfriend, Sluggo. Sluggo is a tough working class kid with no visible means of support, modeled after the slang-talking, newsboy-cap-wearing inner-city kids of U.S. popular culture, akin to Hollywood's Dead-End Kids and Jack Kirby's kid gangs.

This is a fascinating volume, part of a series of themed reprints published by Denis Kitchen during the short-lived Nancy renaissance of the 1980s, when everyone from Frank Miller to various Underground and RAW alumni were singing the praises of the so-called 'dumbest comic strip' ever. One of the best parts of the book is the introduction by reclusive control freak, painter and RAW Magazine cartoonist Jerry Moriarty. Moriarty sums up the appeal of Nancy for the Underground generation as "brain repair," noting that "[b]eing a reluctant Ernie Bushmiller fan also said something about esthetic renewal and ongoing change and hope." Moriarty's essay is accompanied by notes from his alter-ego, Jack, of "Jack Survives" fame. The conceit of this Jack piece is that Jack has been a living in Nancy's town and has observed her adventures with Sluggo from a distance, although he sometimes feels like he is observing something resembling the activity of another dimension, perhaps the creation of his elderly neighbour Bushmiller.

The strips in How Sluggo Survives seem to have been chosen for the degree to which they reveal aspects of Sluggo's life away from Nancy. Many intriguing snippets of his existence are revealed, including Sluggo's address (140 Drabb St.), his various jobs (office boy, delivery boy, scrap dealer, grifter, goldbrick), and portents of his future --a recurring gag revolves around the fortunes he receives from one of those "weight and fortune" amusements that used to litter the commercial districts of every town in North America. Sluggo is a fascinating, mysterious character: a proto-punk hobo child who oozes America from every inky line.

Since I grew up largely post-RAW, I've always taken for granted the canon-icity of Nancy and so the Nancy naysayers and those who argue that Bushmiller's strip is moronic (or even those who appreciate Nancy in an ironic or, "so bad it's good" sense) have always puzzled me. The strip is well-crafted, charming, and, more often than not, very funny and thought-provoking. Highly recommended!

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Superboy Fan Letters Will Blow Your Mind

I accidentally left a copy of Superboy #185, a giant-size 100 page anthology comic from 1972, lying on the kitchen table earlier tonight. For some reason, Kara picked it up and started thumbing through it. I came across her several minutes later. She was sitting abjectly, in something resembling a catatonic state, the letters page from the issue open before her. The cause of her apparent stroke? A letter from Gary Skinner of Columbus, Ohio:

Dear Mr. Bridwell,

It may be a whole year before I can regain my honor, but I have new evidence which will at least allow us to share the blame, with neither of us the loser. The subject is my letter in the Giant Superboy #174. I knew darn well that more had been done to the Kents in the story of their deaths than the elimination of their glasses and the altering of their hair color. They were definitely changed to look more youthful and the change was an artistic one. I looked through the original story in Superman #161, and the difference was there, miniscule though it was. In the reprint, the Kents' necks had been redrawn to be slim, whereas the original had portrayed them as old people with husky, fat necks. I lose in my assumption that Al Plastino himself had redrawn the, but you lose also , because in rejuvenating them, you definitely redrew them, as I maintained. I am exonerated.

By the way, you blew something else on the same letter page. You are supposed to be the authority on the Superman family and all details thereof, but you forgot something concerning the the enlarging of Kandor. Although I cannot quote the magazine or issue from which I got my information, I recall that Brainiac built his shrinking ray in a special way, in combination with his own design of enlarging ray. Such are the conditions that only Brainiac's own ray can enlarge the city to normal without side-effects. Superman himself hasn't been able to duplicate that ray exactly, and even though Brainiac has been disassembled, so sophisticated a computer was he that the memories within his brain are locked there in defiance of any probing ray that might try to extract them. The secret is his alone, and until Superman can get around that little obstacle, the city of Kandor will be dinky as ever. Too bad.

I guess I've henpecked you enough for one day. And at the risk of sounding sarcastic, keep up the good work.

The lesson here is twofold: old Superboy comics have a Kryptonite-like effect on those unfamiliar with the minutiae of the Silver Age mythos and the fannish compulsion to know all. As well, we learn that the fan culture of 1972, as fostered by uber-fan E. Nelson Bridwell, was as vibrant and probing as any in existence today, whether obsessing over the age of Jonathan and Martha Kent --rejuvenated in 1968 (Superboy #145)-- or the nature of Brainiac's nefarious technology.

A final note: Al Plastino lives!

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

"Why even bother drawing Supergirl in such a way that a discussion of her underwear wearing habits is even necessary?"

I guess this is where I say modern superhero comics suck and are mostly ugly.

Gary Panter's art is ugly but is also beautiful.

The title quote comes from comments on this old blog. I am grateful to the Publishers Weekly comics blog, The Beat, written by the venerable Heidi MacDonald, for her 63 comment-generating, quizzical post about a recent comic book cover featuring the Supergirl character. The character is featured in one panel within the comic in question. The panel also features the welcome return of Streaky, the Super-Cat. It's no Jim Mooney classic, but it will do. I'm still baffled by the post (and I even read the comic in question --which does not feature underwear, you may be glad to know).

Well, at least people are talking about something important, instead of the Wright Awards.

Monday, August 18, 2008

I Re-Cruited Some Grem-lins

Well, this looks pretty fucking amazing. Renegade: The Lives and Tales of Mark E. Smith promises to be the greatest Fall-related tome since Pan by Camden Joy or maybe Smith's own lyric collection, VII. The Exclaim! piece includes an embedded video of the Fall's cover of "Victoria" by The Kinks. The Youtube version of "Wings", one of my favourite 1980s music videos, is unavailable as an embed, apparently, but I happily substitute the live version below. I really can't recommend enough the jumbled images of notorious alleged squirrel killer Smith as filmed from the mosh pit sleepwalking himself through this number. On the subject of comics, you can read Smith here. He is a fan of Luther Arkwright and a detractor of "VIZ comic". My own opinion is that VIZ rocks (rocked?) and that Luther Arkwright is overrated.

I feel like this should go without saying, but: watch out for those time-locks!

---

more

Monday, August 04, 2008

Radio Humour

Is it a Mystery Hoard if there is only one item in the hoard?

I found this magazine in the store around the corner, among an assorted batch of old magazines and newspapers. The owner of the store wanted to give it to me, but I eventually talked him up to $2.

This issue of Radio Craft, dated December 1944, was published and edited by Hugo Gernsback, the so-called "godfather of American science fiction." Gernsback was an early fan of radio and a very early adopter of television, as the cover to this issue attests. The Gernsback-penned cover feature outlines "the technique of a remote controlled robot machine gun," designed to address "the desire of all military authorities of the belligerent armies to conserve human life as much as possible" --this in the middle of WWII! The great cover graphic is perhaps one of the first visual representations of a video game precursor (or is it drone warfare?).

This issue also includes several how-to articles written for the radio hobbyist and professional, with special attention given to military issues. There are many wiring and circuit diagrams that confound me.

The best feature of the magazine, from my point of view, are the two radio-themed cartoons by Frank Beaven, a New Yorker and Humorama contributor and sometime writer. Both cartoons manage to ring fairly lame changes on rather trite stock situations from the cartoonists' gag bag. The first cartoon, showcasing the standard offensively racist "captured by African natives" scenario, is delightfully obscure. Adding to the wonder, the gag is credited to Ed Marles of Chilliwack, BC --making this entry eligible for inclusion in the Canadian Comic Fan Project.

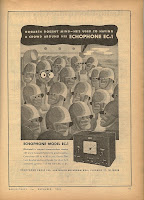

The rest of this issue of Radio Craft is filled out with some wonderful Second World War ads with excellent illustrations, like the inside-front-cover ad for the first cell phone that paints a hellish picture of war by throwing in everything but the kitchen sink and stars a Henry-Fonda-type dogface GI barking into one of those great old Motorola walkie-talkies. The second ad, hawking the Echophone EC-1 radio, is a highly-stylized episode in the adventures of Hogarth, the pop-eyed radio nerd and Echophone spokes-cartoon. World War Two was really a golden age!

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Super Mom

by BK Munn

In honour of the 70th anniversary of the appearance of the Superman character in comic books, Mystery Hoard presents the first in a series of reflections on the Superman influence in comics.

"Richie Rich, the Poor Little Rich Boy in Super Mom"

Richie Rich Millions #45

January 1971

I bought this comic as part of a small Mystery Hoard at a local antique mall. Antique malls are an interesting source of Hoards --it is rare to find a large selection of comics in such places. Rather, small collections are usually offered by individual dealers, as found, more or less in the beat up, random state they were discovered at an estate sale or auction. I suspect this is the situation under which I found a small selection of Harvey Comics titles recently, as I browsed through the mall, with one eye peeled for old Little Dot comics. The Dot comics were intended as a joke birthday gift for a relative who had fond memories of the character from childhood. Imagine my pleasure, then, when I discovered this collection, which contained among other things an issue of Little Dot's Uncles and Aunts. As well, the collection contained this issue of Richie Rich Millions, featuring the titular character and a hodgepodge of his fellow Harvey "stars" like Little Lotta, Dot, and Wendy, the Good Little Witch.

Every Richie Rich story is the story of hyper-capitalism gone wrong. Richie, "the poor little rich boy," is the freakish, hypercephalic hero of a fantasy world that combines the kid adventure scenarios of Little Lulu and Casper with a nightmarish, Dick Sprang-like parody of Scrooge McDuck-style wealth. In Richie's world, people fly around in solid gold helicopters and eat off of disposable dishes made of giant diamonds. Parodied successfully in Dan Clowes' wonderful "Playful Obsession" strip of some years back, these stories represent a childish or pre-capitalist conception of wealth and power: the child reader for whom 25 cents represents a small fortune sees in the "money to burn" universe of Richie Rich a reflection of their own dream of mobility, power and adulthood.

"Super Mom" is a typical Richie Rich outing in that it involves the core members of the Rich clan, including Richie's father and mother (missing is the family butler Cadbury) in a short adventure that takes place in the Rich mansion. The story combines the standard Richie Rich plot device of staggering displays of cartoon wealth with a minor mystery and a punchline "payoff", also involving a joke on wealth or money. Where this story deviates from the norm is in its Oedipal theme and in the presence of the superhero plot device.

Richie's opening salutation to his mother, who is clad in a supergirl costume for a costume party, reads like dialog out of an adult film and we can't help but notice along with Richie, perhaps for the first time, that the voluptuous curves of Mrs. Rich do seem to lend themselves to the wearing of superhero tights (and that Richie's thick-ankled go-go boots look much more fetching on a woman). Nor can we help but notice the impish glee Richie evinces at the sight of his mother's rapidly retreating, yet still magnificent, blue bikini-clad buttocks.

While the creepiness of Richie Rich is legendary, the sexual aspect of the character is the least often acknowledged, although the obvious phallic nature of his monumental obsessions and his overcompensating, moronic displays of wealth and gestures of charity all combine to form a picture of Freudian perversion.

The essential plot of "Super Mom" is similar to typical mystery stories involving iterations of the classic Superman and Superboy characters. Very often, members of the Superman family would develop superpowers or engage in what appear to be superheroic feats, only to have the hero figure out that there is a completely logical explanation. Thus, Ma Kent might be compelled to act as a costumed bankrobber until Superboy figures out she is being controlled by gangsters, etc. In a sense, this Scooby-Doo style plot is the basic premise of most children's mystery comics.

Although Richie was to appear as a superhero in later adventures, this seems to be the only instance of his mother exhibiting super-powers. Her abilities are never mentioned again, even after, in the story's denouement, it is revealed that she has developed super-strength through the constant, life-long wearing of heavy jewelry (were children ever amused by this?).

In honour of the 70th anniversary of the appearance of the Superman character in comic books, Mystery Hoard presents the first in a series of reflections on the Superman influence in comics.

"Richie Rich, the Poor Little Rich Boy in Super Mom"

Richie Rich Millions #45

January 1971

I bought this comic as part of a small Mystery Hoard at a local antique mall. Antique malls are an interesting source of Hoards --it is rare to find a large selection of comics in such places. Rather, small collections are usually offered by individual dealers, as found, more or less in the beat up, random state they were discovered at an estate sale or auction. I suspect this is the situation under which I found a small selection of Harvey Comics titles recently, as I browsed through the mall, with one eye peeled for old Little Dot comics. The Dot comics were intended as a joke birthday gift for a relative who had fond memories of the character from childhood. Imagine my pleasure, then, when I discovered this collection, which contained among other things an issue of Little Dot's Uncles and Aunts. As well, the collection contained this issue of Richie Rich Millions, featuring the titular character and a hodgepodge of his fellow Harvey "stars" like Little Lotta, Dot, and Wendy, the Good Little Witch.

Every Richie Rich story is the story of hyper-capitalism gone wrong. Richie, "the poor little rich boy," is the freakish, hypercephalic hero of a fantasy world that combines the kid adventure scenarios of Little Lulu and Casper with a nightmarish, Dick Sprang-like parody of Scrooge McDuck-style wealth. In Richie's world, people fly around in solid gold helicopters and eat off of disposable dishes made of giant diamonds. Parodied successfully in Dan Clowes' wonderful "Playful Obsession" strip of some years back, these stories represent a childish or pre-capitalist conception of wealth and power: the child reader for whom 25 cents represents a small fortune sees in the "money to burn" universe of Richie Rich a reflection of their own dream of mobility, power and adulthood.

"Super Mom" is a typical Richie Rich outing in that it involves the core members of the Rich clan, including Richie's father and mother (missing is the family butler Cadbury) in a short adventure that takes place in the Rich mansion. The story combines the standard Richie Rich plot device of staggering displays of cartoon wealth with a minor mystery and a punchline "payoff", also involving a joke on wealth or money. Where this story deviates from the norm is in its Oedipal theme and in the presence of the superhero plot device.

Richie's opening salutation to his mother, who is clad in a supergirl costume for a costume party, reads like dialog out of an adult film and we can't help but notice along with Richie, perhaps for the first time, that the voluptuous curves of Mrs. Rich do seem to lend themselves to the wearing of superhero tights (and that Richie's thick-ankled go-go boots look much more fetching on a woman). Nor can we help but notice the impish glee Richie evinces at the sight of his mother's rapidly retreating, yet still magnificent, blue bikini-clad buttocks.

While the creepiness of Richie Rich is legendary, the sexual aspect of the character is the least often acknowledged, although the obvious phallic nature of his monumental obsessions and his overcompensating, moronic displays of wealth and gestures of charity all combine to form a picture of Freudian perversion.

The essential plot of "Super Mom" is similar to typical mystery stories involving iterations of the classic Superman and Superboy characters. Very often, members of the Superman family would develop superpowers or engage in what appear to be superheroic feats, only to have the hero figure out that there is a completely logical explanation. Thus, Ma Kent might be compelled to act as a costumed bankrobber until Superboy figures out she is being controlled by gangsters, etc. In a sense, this Scooby-Doo style plot is the basic premise of most children's mystery comics.

Although Richie was to appear as a superhero in later adventures, this seems to be the only instance of his mother exhibiting super-powers. Her abilities are never mentioned again, even after, in the story's denouement, it is revealed that she has developed super-strength through the constant, life-long wearing of heavy jewelry (were children ever amused by this?).

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Most Expensive Comic Book Ever, Part II

I take it back. A while ago I wondered if this Taschen collection of Robert Crumb sex stories was the most expensive comic book ever. This week, Gary Panter launched his new book, appropriately titled Gary Panter. Published by Dan Nadel's excellent Picturebox, the book is billed as "an intimate look at the work and life of a legendary artist," this massive, wonderful-looking, 688-page retrospective collects comics and images from one of my favourite artists and a close competitor for the previously-bestowed-on-Crumb honorific, "greatest living cartoonist." He certainly is one of the nicest cartoonists ever, as I found out when he signed a book for me during his brief appearance at the Toronto Comic Art Festival a few years back.

I can't wait to see a copy of this "in the flesh". Interested parties can pick up a copy for a measly $95. Supremely interested parties can acquire a copy, along with a limited silk-screen print, signature, doodle, and hand-painted slip-case, for $1000.

Saturday, May 03, 2008

Wonder Woman Costume and Supergirl Underwear

I just noticed that the ads that appeared at the top of my last post were for Wonder Woman Costumes and Supergirl Underwear and Loungewear. I feel that, if I acheive nothing else with the Mystery Hoard blog, I will have the pleasure of knowing that readers have been offered such essential, life-enhancing products as a result of my efforts.

Thursday, May 01, 2008

Solomon Grundy and the Animated Corpse of the Working Class

The Animated Corpse of the Working Class

by BK MunnWe search in vain for examples of the working class superhero. With few exceptions, he is nowhere to be found. In his place, everywhere we find the figure of the superhero working on the side of the bosses, whether as an ideological footsoldier in the armies of the mass media (the Daily Planets and Bugles, WHIZ's and WXYZ's), as a representative of the Repressive State Apparatus (the police and armed forces), or even as the boss himself: we need not enumerate how many capitalists seem to moonlight as masked vigilantes, erstwhile Robin Hoods reduced to acting as night watchmen over the money bins of their fellow billionaires.

Ah, but who do they guard against? Who appears to play the role of Beagle Boy opposite the concerted efforts of these super-powered Scrooge McDucks? The superhero's triumphalist rhetoric of truth, justice, and the American Way must not remain unchallenged --nor can the use of force continue to be monopolized by a single comic book class. At last, a dim figure steps forward to take up its historic role of class antagonism.

Enter the supervillain, shambling leftward onto the world-historic stage. As an expression of class anxiety, he is unparalleled in art. From his secret origins as the stepchild of the mustache-twirling Oil Can Harry of melodrama and the grand-guignol grotesques of Dick Tracy, the comic book villain embodies all of the perceived threats to the capitalist utopias envisioned by the comic book creator, a world of shiny metropolises, lorded over by masonic fraternities of top-hatted magicians, fetishistic playboys, and patriarchal circus strongmen.

The supervillain disturbs this child-like Eden by introducing a note of the abject to the proceedings. The supervillain, representing the poor and working class multitude, is our window into the world of the superhero. Whether mad-scientist, gun-toting mobster, or costumed gadgeteer, the comic book villain represents "the return of the repressed" in the dream world of adolescent power fantasies. No matter how often or how ingeniously the superhero puts him down, the villainous representative of the working class schemes his way out of his prison and into a new museum heist, nuclear extortion, or revenge plot. The chief lesson of the superhero narrative is that no plot device or deus ex machina can ultimately contain the immense power of the working class, especially when organized or constituted as a corporate mass entity.

The appeal of their forceful presence is almost magnetic. What youthful reader has not experienced a comradely thrill when encountering for the first time such deliciously named amalgamations as The Monster Society of Evil, The Legion of Doom, or The Secret Society of Supervillains? These unions and guilds of the downtrodden lumpen proletariat of the comics form an essential counterpoint to the legalistic Chamber of Commerce-like aura that adheres to the clubby superhero organizations (The Justice League of America, The Avengers, et al).

Nowhere is this more evident than in this charming little epic from 1947's All-Star Comics #33. The two post-War years of 1946 and 1947 were memorable as a time of intense class conflict, as the wartime economic boom combined with an increasingly militant U.S. working class made up of returning soldiers and a Depression-hardened nation. Some of these issues are bound to find their way into the prole art form of comics.

Nowhere is this more evident than in this charming little epic from 1947's All-Star Comics #33. The two post-War years of 1946 and 1947 were memorable as a time of intense class conflict, as the wartime economic boom combined with an increasingly militant U.S. working class made up of returning soldiers and a Depression-hardened nation. Some of these issues are bound to find their way into the prole art form of comics."The Revenge of Solomon Grundy" features the return of the nursery-rhyme-inspired supervillain Solomon Grundy, after a long absence. Last seen imprisoned by Green Lantern in a magical green ball, Grundy personifies the bottled-up desire of working class ambition, on hold during the "no-strike" years of World War II and still frustrated by the years of the Great Depression of the 1930s. At the same time, he represents the refusal of the disciplinary regime of the social factory system --a sort of unliving mass strike.

Grundy's attributes are those of the dreaded poor or proletariat unleashed. From his humble origins as a small-time criminal who meets his ignoble end drowned in a swamp, to his reincarnation as a monstrous, barely articulate agent of vengeance, Grundy is a proto-Hulk, equal parts lovable hillbilly and Luddite loom-smasher. Clad in tattered working-man's clothes, including giant hobnail-style brown boots, the zombie-like Grundy stands in stark sartorial contrast to the dandified glamour of the superheroes, with their capes, primary colours, and bold trademarked insignia. He is the Other to the rich and powerful superhero, a dialectic whose hallmark is violence and confrontation.

Grundy's attributes are those of the dreaded poor or proletariat unleashed. From his humble origins as a small-time criminal who meets his ignoble end drowned in a swamp, to his reincarnation as a monstrous, barely articulate agent of vengeance, Grundy is a proto-Hulk, equal parts lovable hillbilly and Luddite loom-smasher. Clad in tattered working-man's clothes, including giant hobnail-style brown boots, the zombie-like Grundy stands in stark sartorial contrast to the dandified glamour of the superheroes, with their capes, primary colours, and bold trademarked insignia. He is the Other to the rich and powerful superhero, a dialectic whose hallmark is violence and confrontation.The plot of the story is delightfully simple. Freed from his magical prison by a stray bolt of lightning, Solomon Grundy rampages through the countryside and a series of small towns in search of his arch-enemy, the superhero Green Lantern. Alerted by a radio report, the members of the Justice Society disrupt their monthly meeting and split up to search for the so-called "inhuman menace to mankind." Encountering Grundy separately, the members of the Society suffer defeat after defeat, but manage to each solve a number of local dilemmas brought to light by the appearance of the ghostly apparition of Grundy. Thus, the sound thrashing administered to The Flash is the occasion for a local police chief to redeem himself. Likewise, Dr. Midnight's narrow escape from death at the hands of Grundy results in his foiling a pair of safe-crackers.

The locus of the action is largely industrial, with all of the settings having heavy ideological overtones. For instance, the heroes battle Grundy in two factories: Diminutive college student-turned costumed pugilist The Atom engages his opposite inside a shoe factory, where versions of Grundy's giant boots are arranged in rows and the giant seizes the means of production, as it were, to deliver a major beating. In a similar manner, Johnny Thunder encounters a copy-cat version of Grundy at a cereal factory. The other heroes attempt to prevent Grundy's riotous war on private property in the form of a town square, a rich family's mansion, and a newspaper office, with mixed results.

The solution is total banishment: the lesson of the comics is that Grundy, aka the working class, cannot be stopped by bullets or brawn. It remains for Green Lantern to encase him in another bubble and transport him to the moon, in something of an anti-climax.

It is easy, given stories like this, to imagine Solomon Grundy as a mass or corporate figure, his part-human, part-swamp composition a dual metaphor for both the imagined threat posed by an aroused working class --a working class that can only be constrained by a concerted effort on the part of capital, utilizing all of capital's weapons-- and a repressed proletarian subjectivity, reveling in freedom and destruction. In this respect, even the efforts of a penny-a-word pulp writer like Gardner Fox and a team of teenage artists employed in sweatshop-style production, labouring over adventure stories for children, have a part to play in the ideology and iconography of class struggle.

It is easy, given stories like this, to imagine Solomon Grundy as a mass or corporate figure, his part-human, part-swamp composition a dual metaphor for both the imagined threat posed by an aroused working class --a working class that can only be constrained by a concerted effort on the part of capital, utilizing all of capital's weapons-- and a repressed proletarian subjectivity, reveling in freedom and destruction. In this respect, even the efforts of a penny-a-word pulp writer like Gardner Fox and a team of teenage artists employed in sweatshop-style production, labouring over adventure stories for children, have a part to play in the ideology and iconography of class struggle.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Unsung Geniuses: Florence Thomas of ViewMaster

by BK Munn

Most fans of the tiny fantasy worlds glimpsed through the lens of a View-Master viewer are probably unaware of the name Florence Thomas. Thomas was the Portland, Oregon sculptor employed by the makers of the 3-D viewer to create miniature dioramas of fairy tales and pop culture scenes which she then photographed for reproduction into the iconic circular white reels that have delighted children and adult collectors for decades.

Thomas produced her first reels for View-Master in 1946 --a series of Fairy Tales and Mother Goose rhymes that are still in circulation. According to one source, Thomas "developed special methods of close-up stereo photography and modeling which is now in common use by major motion picture studios" (John Waldsmith, Stereo Views, 1991). She created scenes of such detail and attractiveness that you feel you could step inside and look around a corner at a complete world. Besides the Fairy Tales, these worlds included versions of the Frankenstein and Dracula stories, scenes from the comic strip Peanuts, and 3-D versions of animated cartoons like The Flintstones. Amazingly, all of the puppet-like figures were sculpted from clay and the scenes were shot using a single-lens camera (not a stereo camera) that was moved on a track to get the stereo shot. Sometimes the models were moved slightly between shots to enhance the 3-D effect. During her heyday, Thomas appeared on television and radio to satisfy the curiosity of the children who consumed View-Masters by the millions in the 1950s and 60s. Today, she is largely forgotten except for a few collectors. You can see her at work (in 3-D, of course!) on this collector's reel. A tv appearance is available on this dvd.

Thomas trained a successor, Joe Liptak, seen below shooting a scene from the Disney Robin Hood set. The work of these two geniuses, lovingly crafted three-dimensional stories, live on in the creations of artists like Vladimir, recently profiled in The Believer magazine.

Monday, April 07, 2008

Andy Warhol is ... Robin the Boy Wonder!

From a Batmania-era issue of Esquire magazine, a photo layout of Andy Warhol dressed as Robin and Nico dressed as Batman. Lester Bangs said that Nico was sort of a racist dunce, but she is such an intense vision and one of my favourite singers ever.

(via Jeff Trexler)

Tuesday, April 01, 2008

Jim Mooney, Classic Supergirl Artist

Jim Mooney, 1919-2008

by BK Munn

Wow, less than a week after the amazing news that the Siegel estate has regained the Superman copyright comes the sad news that cartoonist Jim Mooney, one of the last remaining artists of the classic Superman Family stories, has died. Mooney died on Sunday, March 30, according to this obit by Mark Evanier.

Mooney was best known for his long association with Supergirl --he illustrated her adventures from roughly 1959 to 1969. Along the way, he was also responsible for delineating many of the most fondly-remembered adventures of the Legion of Superheroes. In the 1970s, Mooney moved to Marvel and worked on Spider-Man, Ms. Marvel, and, most famously, Steve Gerber's Man-Thing and Omega the Unknown.

Mooney's Supergirl art developed into a perfect match for the character, with soft lines and many feminine details --like the trademark long eyelashes and frilled skirt he added to the character. At DC, Mooney usually inked his own pencils, controlling every aspect of the finished art. (In contrast, Mooney would usually work either as a penciller or inker when at Marvel, finishing pencils by Romita or John Buscema and being inked by Frank Giacoia).

Before he landed the Supergirl gig, Mooney had drawn humour, girl and funny animal comics, eventually moving on to adventure comics including ghosting Dick Sprang on Batman and illustrating Tommy Tomorrow and Dial H for Hero. His style on Supergirl is in strong contrast to the other Superman artists of the period. These artists (Curt Swan, Al Plastino) preferred muscular, dynamic figures and slick inking. Even Mooney's closest parallel, Lois Lane artist Kurt Schaffenberger, had a slick style with more in common with strip cartoonists like Alex Raymond and Mandrake the Magician's Phil Davis. Mooney's female figures are delicate and his teenagers look like teenagers, not smaller versions of adults. He also had an eye for the humourous, and was responsible for some great goofy aliens and one of the most memorable aspects of the Supergirl strip, Streaky the Super-Cat. According to an 2005 Daniel Best interview printed in TwoMorrows' Krypton Companion, "Streaky the Super-Cat was my design. I think the writer came up with initial idea, but I designed him so he looked a bit more like an animated cat. I fell in love with Streaky from the very beginning. I still draw him. I love cats. But instead of the editor telling me, 'Make him look like this.' or 'Look like that,' I pretty much drew him my own way."

Mooney's cartoon realism blend was the perfect fit for the Supergirl series. While not of the order of Ogden Whitney's bizarre, frozen art style, Mooney compositions and figures often had an underwhelming, pedestrian edge, in keeping with the sometimes low-key adventures of Supergirl. The off-putting, melodramatic premise of the series, that the orphan Supergirl is kept as a secret weapon by Superman, forced to live in an orphanage until she masters her superpowers and can be revealed to the world, resulted in many stories that merely retread ground already covered by Superman and the Smallville-bound Superboy. Thus, like Superman, Supergirl is tested by the Legion of Superheroes and has a mer- love interest. She wears a wig and uses a loyal robot double, stored in a hollow tree until needed (surely, one of the saddest aspects of any comic book ever!). Many of Supergirl's Midvale adventures revolve around the world of highschool and high-school romance. Mindful of the intended female audience for the character, the writers along with editor Mort Weisinger, found many opportunities to threaten Supergirl with marriage to strange aliens or have her develop crushes on cowboys who are really magic flying horses transformed from ancient Greek centaurs.

Conversely, Mooney was responsible for some interesting science fiction imagery and was adept at fanciful costume design --he drew hundreds of costumes for both the Legion of Superheroes feature and the Dial H for Hero back-up. Mooney is responsible for the look of many popular Legion characters including Chameleon Boy, Invisible Kid, Colossal Boy, Triplicate Girl, Phantom Girl, Brainiac 5, Shrinking Violet, Sun Boy, and Bouncing Boy.

Mooney's characters were capable of expressing a broad range of emotion. While the plots of many Supergirl stories often resembled those of romance comics, the fear, sadness and love that the characters expressed facially and the approach to body language, ranging from delicate hand gestures to slapstick double-takes, were unique to comics. On an average page, Supergirl/Linda Lee was likely to move from wide-eyed excitement to creased-brow worry to blissful dreaming to eager determination.

These are some of my favourite children's comics, a beautiful body of work created by Jim Mooney, a skilled, professional artist, who worked in tandem with great writers like Otto Binder and Superman's co-creator, Jerry Siegel.

-----

A gallery of Supergirl commissions by Mooney.

500 pages of Jim Mooney's Supergirl for $15.

The origin of Streaky.

A gallery of Mooney covers.

Superman robots

Super-Mom

Monday, March 31, 2008

Is This the Most Expensive Comic Book Ever?

Robert Crumb's Sex Obsessions

Taschen Books

258 pages

$700

I saw this beautiful book at the Beguiling last week and can't stop thinking about it. Compiling 14 of Crumb's best sex-obsessed stories published between 1980 and 2006, hand-colored by Pete Poplaski, this book may not only be the most expensive, but also, quite simply, the best comic book ever. Crumb is our greatest living cartoonist, and this represents some of his greatest mature work.

It also made me wonder, is Taschen the best comic book publisher ever?

Full details here.

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

Monday, March 24, 2008

Graphic Novel Review: Skim

Skim

words by Mariko Tamaki

drawings by Jillian Tamaki

Groundwood Books/House of Anansi Press

143 pages

$18.95

review by BK Munn

This gorgeous new graphic novel answers the question, what if 80s sitcom The Facts of Life was really a drama about Wiccan ceremonies, lesbian crushes, casual racism, and suicide?

Sixteen-year-old diarist Kimberley Keiko Cameron (aka Skim) is already having a hard time negotiating the preppy world of her Catholic all-girls school when she is plunged headfirst into adulthood. For Skim, "being sixteen is officially the worst thing I've ever been." Like every teenager, alternately bored, embarrassed, and confused, Skim tries several strategies to forge a unique identity for herself, with little success. Even the goth subculture Skim imagines as a refuge from the lameness of her middle class surroundings turns out to be one big letdown. In one of Skim's funniest sequences, the cult of adult Wiccans Skim and her best friend Lisa join turns out to be little more than an AA support group for hooking up burned-out ex-druggies.

The suicide of a cheerleader's boyfriend sets the plot of the book in motion and brings into focus the cracks behind the facade of highschool innocence, friendship, and Skim's own ironic distance from her own emerging womanhood and adult awareness. As her school becomes obsessed with death and suicide, Skim argues with and eventually drifts away from her best friend, moving towards new relationships and her first romance (with hippie English teacher Ms. Archer).

Skim is a delicious balancing act between words and pictures, with Skim's studiously deadpan narration contrasted and enlivened by Jillian Tamaki's fluid drawing style. Luxurious panels, alternately spartan and highly detailed, depending on the story's mood and dramatic necessity, take us step-by-step through every moment of Skim's experience. There are almost no false notes in this book, graphically or textually, a difficult performance in any work that strives to capture the nuances of teenage interiority and speech patterns.

One of the book's major themes is the series of disappointments with the adult world that adolescence is fraught with. Skim progresses through disillusionment after disillusionment, but is luckily girded with the twin weapons of sarcasm and a practiced ability to fade into the background. But these tools are almost not enough to guarantee her survival when she is forced to experience firsthand the heartache she has previously only been a sardonic observer to. In the course of the book, Skim is drawn inexorably into adulthood through a gamut of betrayals and epiphanies, all of which she faithfully chronicles for us.

The conceit of the book is that the visual aspect represents a drawn diary --the unconscious working in tandem to give a (literally) well-rounded picture of Skim's experience. Textually, this takes the form of crossed-out confessions, list-making, and subtle, funny observations expressed as Zen equations ("me=seriously screwed"; "my school=goldfish tank of stupid"). Graphically, the pictures often take the story beyond the diaristic, a perfect use of the comics form, showing what Skim can't bring herself to confess verbally through the use of body language and tiny facial expressions; skilled use of black and white, chiaroscuro effects, gray washes, and easy, virtuoso line-work. Certain key scenes are entirely wordless and Jillian Tamaki's visual storytelling skills are utilized to the maximum with almost surreal effect.

An early version of Skim was published by Kiss Machine in 2005 and writer Mariko Tamaki reworked the story as a play before the graphic novel version took its current shape. The minimalist prose, humour, and tight structure of the book seems to be a result of this process, filtered through the eye of Jillian Tamaki. The whole effect is a darkly funny, bittersweet coming of age story.

--------

Skim Booklaunch

This Is Not A Reading Series

Wednesday, March 26th. 7:30-12pm

The Gladstone Hotel, Toronto

Free

Mariko and Jillian Tamaki will be interviewed by Toronto writer Jessica Westhead, with Brad Mackay introducing.

Skim news at Jillian Tamaki's blog.

Saturday, March 15, 2008

International Shakespeare in the Comics Day

March 15 is International Shakespeare in the Comics Day!

Top 5 Shakespearean Comics:

1. The Mighty Thor by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

Stan introduced a pseudo-Elizabethan language to this superhero series about Norse gods, lending the dialogue an epic, Shakespearian quality. As well, Kirby's creation of Volstagg, equal parts Falstaff and Porthos of the 3 Musketeers, introduced one of the more interesting secondary characters of the Marvel Universe.

2. Asterix and the The Great Divide

This retelling of Romeo and Juliet the first volume in the Asterix series to be written and drawn entirely by cartoonist Albert Uderzo after the death of his longtime partner Rene Goscinny and is a charming change of pace for Asterix and Obelix.

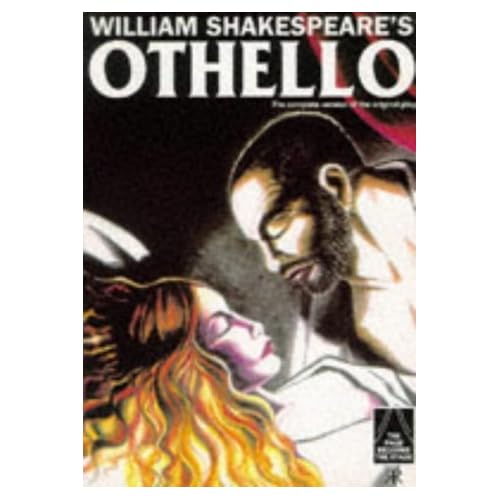

3. Oscar Zarate's Othello

Best know for his collaboration with Alan Moore on A Small Killing, this imaginative adaptation by the Argentinian Zarate is one of the best straight-up comic versions of the original play.

4. Julius Caesar by Wally Wood

The best comics adaptation of Julius Caesar is a parody of the 1954 Marlon Brando film version, illustrated by Wally Wood and written by Kurtzman and printed in MAD #17. MAD loves the bard, but this early piece is the best. Caesar got the full biographical treatment in Frontline Combat #8 (1952).

5. Batman, Dick Tracy and Spider-Man

Hardboiled Hamlets. All three of these characters are essentially revenge dramas (revenge melodramas?). All three are premised on the death of a father figure and the resulting metaphorical relentless, humourless, hunt for a killer. That's all I've got. I'm sure it's more complicated.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)